In the vast repertoire of Indian ornamental motifs, among the symbols and devices that recur in traditional art and architecture, the lotus occupies pride of place. Unlike western art, in which great emphasis is laid on photographic realism and the naturalistic treatment of human and animal forms, the main concerns in Indian art are profoundly spiritual and religious. Each and every object portrayed in Indian art has a religio-spiritual and symbolic significance.

Among the flowers, the lotus is the most preferred symbol, not because of its beautiful form, but because of its profound symbolism. We all know that this flower grows in muddy waters, but remains unaffected by it. Whether white, blue (nilotpala), rose pink or white and pink, its petals evoke the sentiments of purity in everybody’s mind. According to Hindu philosophy, human beings ought to live like a lotus flower in this wily, unscrupulous world, completely detached and pure hearted, untouched by evil forces.

Rising from the depths of water and expanding its petals and leaves on the surface, through its appearance, it gives proof of the life-supporting power of the all nourishing abyss. This is the reason why a lotus flower

in full bloom is used as the pedestal or throne support of all the deities — Hindu, Buddhist and Jain.

Vishnu and Lakshmi Standing on a Lotus Protected by Sheshnag

Invariably, they are shown seated or standing on a fully open lotus flower (padmu pitha) or on a double petalled

lotus (mahambuja). This has symbolic connotations: the deities are represented in their transcendental, subtle forms, i.e. the spiritual body which is weightless. If seated with one leg dangling down, then also the deity’s foot rests upon the lotus pedestal or cushion.

Numerous Hindu deities are shown holding a lotus flower, for example, Vishnu who preserves the universe, is invariably holding the padmu (lotus) in one of his four hands. Vishnu’s spouse Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, Shiva’s consort Parvati, Surya the Sun god, the Bodhisattva Padmapani — all these deities hold a lotus flower in their hands. In fact, even the personified sacred river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna always hold a long stemmed lotus, characterized by a long stalk, the undulations of which match the contours of their elegantly standing ‘S’-shaped bodies.

Wooden Lantern ceiling relived with lotus flowers and an immense lotus rosette in the centre, from the Mandapa ceiling of Chamunda Devi temple, Chamba (Himachal Pradesh), 17th century CE.

In Indian paintings, whether miniature ones or frescoes, the flowing waters of the river or a pond are always indicated by lotus flower and their broad leaves floating on their surfaces. This tradition has persisted from ancient times. In the world renowned Ajanta caves frescoes, the lotus pond is an alluring part of the landscape, and continued to be so in subsequent centuries till the dawn of 20th century.

All the schools of miniature painting that flourished in the royal courts all over India, more especially in Rajasthan and western Himalayas – the latter popularly known as the Pahari School – feature the river front as well as lotus pond in this manner. Lord Krishna and his exploits (lila) were the most popular themes painted with great verve on account of his romantic escapades. In Pahari miniature schools, not only Krishna but all the Hindu deities are featured as sporting pinnacled crowns surmounted by lotus buds.

Painted ceiling from a Cave Temple at Ajanta enclosing lotus flowers within concentric rings of circular mandala, 5th Century CE.

From the period of Ajanta frescoes (2nd century BCE to approximately 7th century CE) onwards, the ceilings are painted with concentric circles enclosing a variety of motifs, the lotus flowers, buds and petals have been painted in mind baffling diversity; each one is different from the other, far more delicate and impressive.

The tradition of chiselling a large lotus rosette in full bloom carved in bold relief, with broad petals, spread out or at times curling in with great delicacy and finesse, is also very ancient. Such ceilings have survived in the rock—cut cave shrines at Ellora, in the 7th century CE timber and monolithic temples in Himachal Pradesh, in Bharmaur and Chhatrarhi in Chamba, at Masrur in Kangra district.

This tradition was not, however, confined to these regions alone, but existed all over India. The central component of the mandapa ceiling in the famed marble Jain temple at Mount Abu in Rajasthan, erected by Vimala Shah in the 11th century CE is a great masterpiece of artistic talent and ingenuity displayed by the local sculptors who produced an exquisitely carved pendulous, filigree-like lotus rosette, that haunts one long after one’s visit to these marvellous shrines. This tradition persisted all through the centuries down the ages. Diverse architectural components in the stone temples have been relieved with lotus rosettes in a variety of ways.

In both the timber and lithic temples, almost all over India, lotus rosettes apart, there are bands of exquisitely carved lotus petals running through the external and interior walls, as also ceilings, separating panels relieved with diverse episodes from the legends pertaining to the deities. The doors display an immense lotus rosette chiselled all over their surfaces. The undulating lotus volutes as well as broad lotus petals contribute to the rich effect of the door frames, the stone and brass uprights of the flaming, effulgent aureoles (prabhavalis) surrounding the icons of worship installed in the inner sanctums of the temples.

The heads of all the deities are also surrounded by a circular halo relieved with eight lotus petals, the numeral eight having a mystical connotation and significance. The undulating, meandering creepers formed by the long drawn out lotus stalk lend elegance and delicacy to many a temple doorway from Kashmir in the north to tip of south India, from Gujarat in east to Orissa in the west.

The tradition of carving immense lotus medallions of roundels enclosing bird and animal motifs harks back to the pre-Christian era when the famous Buddhist stupas were erected at Bharhut and Sanchi. This tradition is not confined to religious architecture alone. It enriches the residential houses of the ordinary natives as well, apart from their depiction on the walls of the royal palaces and forts.

When the Muslim and Mughal rulers got their palaces erected, the native craftsmen continued to use the same motifs to great advantage. In the twin Red Forts of Agra and Delhi, large lotus rosettes made of marble are embedded on the floors, from the centre of which the fountains spouted forth water to keep the palaces cool during the hot, sultry summers of north India.

This motif was not confined to architecture, religious or non—religious, alone; it was profusely used in all forms of crafts. Most embroidered fabrics feature the lotus mandalas in the centre, around which are sprinkled numerous motifs and figures.

In woven and printed textiles as well, in stone and wood carvings, in ornaments worn by women, the lotus rosettes are used with immense innovativeness and imagination. The multi-petalled lotus rosette offered the craftsmen working in all mediums plenty of scope to display their amazing talent, skill and ingenuity. This motif is found ubiquitously in its many splendoured form in all forms of crafts all over India.

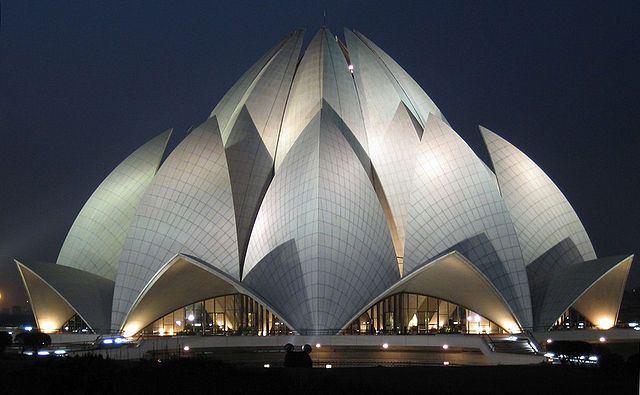

The Lotus Temple, located in New Delhi, India